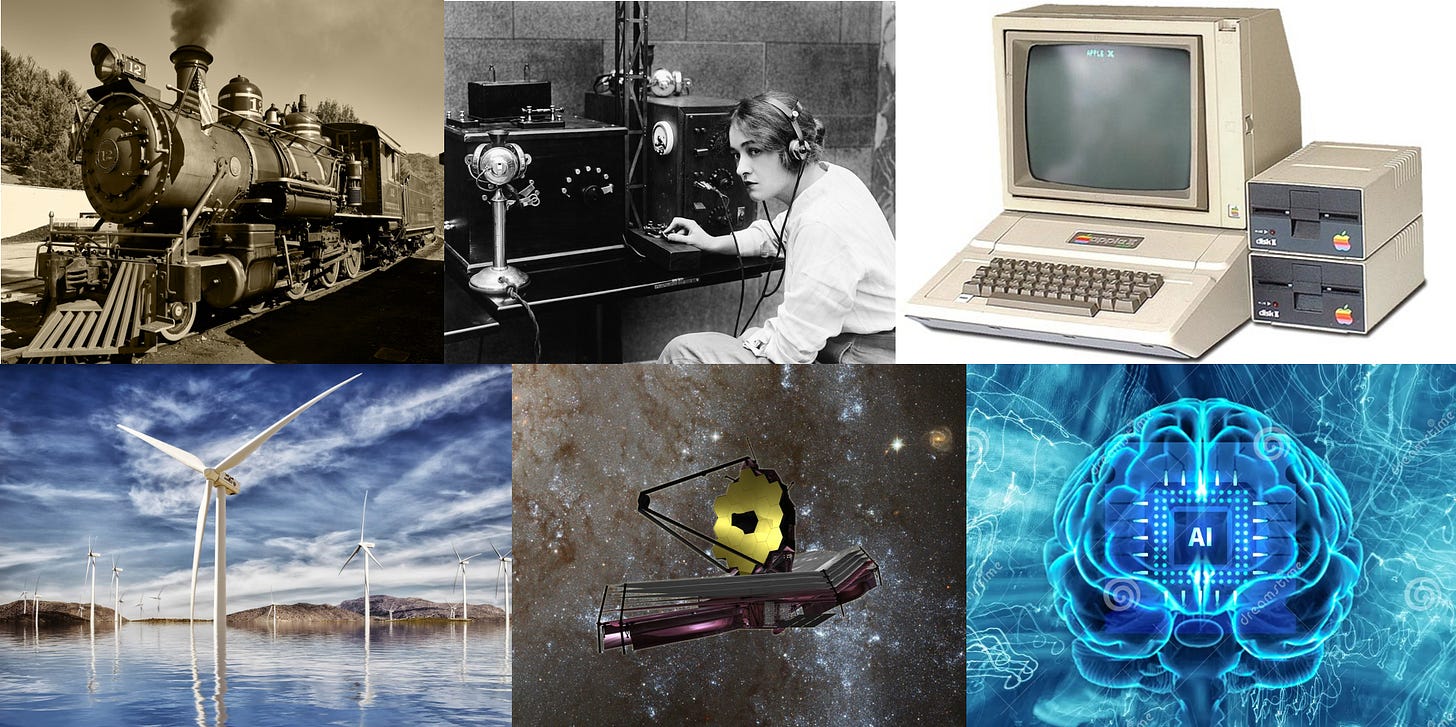

My late Aunt, who took me to her family after my parents had died, and brought me up through childhood and adolescence, witnessed in her life the emergence of radio, television, and cars as life-changing commodities. She introduced me to the world of books, and taught how to talk politely on the landline phone. She wrote letters in longhand, and tried to keep her mind open to popularised science, from cosmology to evolutionary biology. She rather welcomed technological novelties than feared them.

At the time of my senior year at technical college, first desktop computers came into use. I delved into the new technology with all youthful curiosity. Computer-aided design (CAD) software has been my working companion through all life, from the first, hardly an aid, lines on a monochrome display, to advanced, complex 3D models today. Yet my Aunt could not understand how my typing and clicking could be a continuation of the work done in pencil on a drawing board. For her, work with computer was not “real”. She kept reading about black holes and the Neanderthals, but considered a desktop computer, an inscrutable box, an unnecessary device.

I believe that everyone, on his or her path through the technology-infused world, comes to a threshold they will never cross. This apprehension is not because of the lack of intellectual capability to learn a new technology; it is more about the will to remain in the world which seems coherent and complete, as it is.

This apprehension is not because of the lack of intellectual capability to learn a new technology; it is more about the will to remain in the world which seems coherent and complete, as it is.

For me, the threshold I am not willing to cross, is the generative artificial intelligence. In my mind, I refuse to call it “intelligence” at all.

I strongly believe, that specialised large data models may be beneficial and therefore worth developing. It may be sieving billions of possible combinations of molecules to find those viable to become effective drugs. It may be the realm of weather forecast, or prediction of earthquakes; the benefits of better results are indisputable. So I am heart and soul with scientists, who make good use of large data models, and of the processing capability of silicon chip clusters.

At the same time, I reject the big tech visionaries, self-appointed disruptors, who strive to track every thread of my everyday activity, and inundate me with unsolicited prompts they call “intelligent”.

Imagine a colleague at work, who watches whatever you type, and every now and then prompts you how to finish your sentence, usually in a bland, trite manner. How long would you put up with such an intruder? “Mind your own business” would be perhaps your most polite reaction.

Why do we then tolerate Google suggestions on emails? Does it really save your time to hit “Tab” instead of typing your own words to the end, at a steady pace? Do we really need to waste gigawatts of energy to get a prompt “thank you” or “I agree” popped up on our screen? Why does Google read my correspondence at all, in the first place?

We, the human race, on our heavy-loaded planet, have reached the tipping point where we need to slow down.

We don’t need to manufacture more, to travel faster, to churn out more information. Don’t delude yourself that the time you’ll save by letting the algorithm finish your email will help you to do something more worthy. Most likely you’ll only type two unnecessary emails more.

There is a deep wisdom in the notion of “friction”, a force we must overcome in every our action. Will it be the weight of a watering can in your garden, or the force and skill to use a tool in a carpentry workshop. It may be racking your brains on a design, or soreness in the eyes after long writing. An effortless work leaves us dissatisfied, and without effort, the only way we can compensate for the lack of fulfilment is to crave for more, and more, infinitely.

What the big tech false prophets offer us, comes from the mentality of a slave trader. “There is a slave, A.I. algorithm in this case, which will do all the work for you, and I will become rich, when I sell this slave to the millions of you.”

This is a disastrous delusion.

So, what to do?

Facilitate your everyday work, but do not try to eliminate all the friction, all the weight from it. Write letters with your own style; take your time to write every one of them. Search the web and sort out the results by skimming them on your own. Don’t subscribe to any news feeds; read the papers and magazines you trust, and check widely, if they deserve to be trusted. Apply the scrutiny of your human intelligence, reasoning, experience, and discerning, to everything what is offered to you.

Chase away the digital spies and electronic drovers from your life.

I dare to say that throughout my engineering career, I’ve been making a good use of computers, the inscrutable boxes my late Aunt refused to try to understand.

I believe that the generation of my children and grandchildren will find a good way (and, a better name in the first place) for “artificial intelligence”. I envisage its use in science, medicine, materials engineering, climatology, seismology. Provided that it does not make the human intelligence extinct before all the good gets a chance to happen.

If you have any thoughts on the above, please leave a comment. Your remarks may improve my future writing.

Do you think some of your friends might like it? Feel free to share Eyeore Ponders with them:

Thanks for reading; until next time!

Press “like” if you will, it is the kindest expression of encouragement.